Every year I attend the birthday commemoration for General George Gordon Meade. It takes place at the general’s burial spot in Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, and since Meade was born on December 31, it happens on the last day of the year.

Every year I attend the birthday commemoration for General George Gordon Meade. It takes place at the general’s burial spot in Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, and since Meade was born on December 31, it happens on the last day of the year.

Meade’s 202nd birthday in 2017 was certainly the coldest one I’ve attended, with temperatures hovering around 14 degrees. That kept the turnout down a bit, but the hardcores showed up to pay their respects. Andy Waskie, the General Meade Society of Philadelphia’s founder and president, made the wise decision to hold the ceremony inside the cemetery gatehouse, following a quick wreath-laying ceremony at the gravesite.

Andy asked me to be the keynote speaker this year, so I prepared a few appropriate remarks. I started off by remarking that this is certainly an interesting time to be interested in the Civil War. Americans often accused of forgetting their history and sometimes that’s true, but in 2017 activists across the country became very interested in the Civil War.

As a result, statues of Confederate leaders were taken down in cities across the south—in New Orleans, Memphis, and Baltimore. A protest, led by white supremacists and neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, Virginia, over the planned removal of a Robert E. lee statue, led to the death of a young woman.

People get upset that this constitutes some kind of “erasing” of history.

Those of us who follow the life and legacy of George Gordon Meade know what being erased from history looks like.

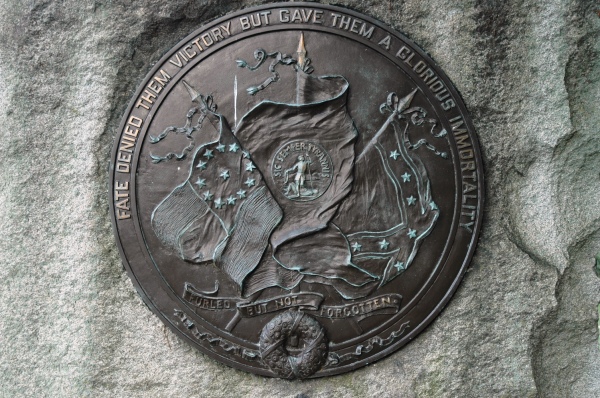

In 1913, 50 years after the Battle of Gettysburg, Meade’s grandson published the generals Life and Letters. A reviewer was moved to note, “For fifty years Meade has been set aside, ignored, depreciated, even insulted.” Meade should have received a bit of immortality for commanding the victorious army at Gettysburg, but instead he mostly disappeared from the history books.

I think there’s little chance that Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart or Nathan Bedford Forrest are in any danger of being “erased” from history.

No, the real erasure began more than 150 years ago, with the creation of the Lost Cause narrative of history. According to this mythology, the South did not secede to preserve slavery. It fought for the noble cause of states’ rights. Never mind that before the war, the southern states pushed through the Fugitive Slave Law, which trampled on both state and individual rights by forcing people across the country to assume the role of slave catchers to help capture people who were trying to escape from bondage.

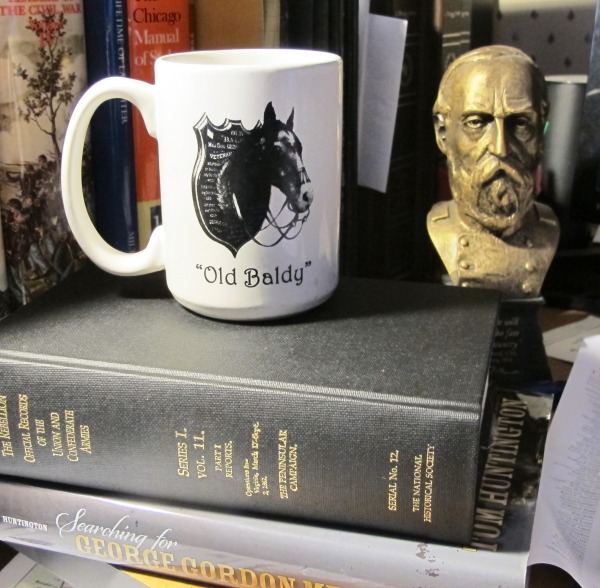

Let me quote Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy. In his famous “cornerstone” speech in March 1861, less than a month before the attack on Fort Sumter ignited the Civil War, Stephens declared that slavery “was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.” Furthermore, he added, the foundation of the Confederate government–its very cornerstone, in fact—“rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” As I wrote in Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg, claiming that slavery did not cause the Civil War is like clearing the iceberg of any responsibility for sinking the Titanic.

Let me quote Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy. In his famous “cornerstone” speech in March 1861, less than a month before the attack on Fort Sumter ignited the Civil War, Stephens declared that slavery “was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.” Furthermore, he added, the foundation of the Confederate government–its very cornerstone, in fact—“rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” As I wrote in Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg, claiming that slavery did not cause the Civil War is like clearing the iceberg of any responsibility for sinking the Titanic.

There’s such a thing as being on the wrong side of history. Jefferson Davis, Lee, Jackson, and other Confederate leaders were on the wrong side. That doesn’t mean there weren’t brave men fighting on both sides during the Civil War. There certainly were. But I think you have to separate the reasons why the common soldier was fighting and the reasons why the southern states seceded and started the war in the first place.

I like to remember the words of Ulysses S. Grant, who, when writing about the surrender of Lee at Appomattox, said, “I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

George Meade was no abolitionist. He fought to save the Union. But when eradicating slavery became official U.S. policy, he continued to do his duty. He was on the right side of history. And that’s why we gathered at Laurel Hill Cemetery on such a frigid December 31. We wanted to make sure that this man—who came close to being erased from the history books—got his due for fighting to preserve the United States of America and, by so doing, helped bring slavery to an end in this country. George Gordon Meade was on the right side of history.

I’ve long wanted to get an excuse to drop in and pay my respects to John Sedgwick, who is buried in Cornwall Hollow Cemetery in northwest Connecticut. It’s a tiny rural cemetery in the middle of nowhere. Sedgwick lies beneath a granite obelisk, one of the most prominent monuments here. On the other side of Rt. 43 from the cemetery is a fairly impressive monument to Sedgwick, with a granite obelisk, bronze profile, cannon, and stacks of cannonballs at the corners. I wonder how many people who drive past it have any idea who Sedgwick was.

I’ve long wanted to get an excuse to drop in and pay my respects to John Sedgwick, who is buried in Cornwall Hollow Cemetery in northwest Connecticut. It’s a tiny rural cemetery in the middle of nowhere. Sedgwick lies beneath a granite obelisk, one of the most prominent monuments here. On the other side of Rt. 43 from the cemetery is a fairly impressive monument to Sedgwick, with a granite obelisk, bronze profile, cannon, and stacks of cannonballs at the corners. I wonder how many people who drive past it have any idea who Sedgwick was.

You have only one chance to turn 200. And now George Gordon Meade has done it.

You have only one chance to turn 200. And now George Gordon Meade has done it.  I was honored to be one of the speakers. I kept my remarks brief (to the palpable relief of the crowd). I quoted William Faulkner, who once said, “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.” I remarked on the irony of how easy it is to realize the truth of that when you’re in a historic cemetery where all the figures from the past are indisputably dead. But the history they helped create is a living thing, and the events involving these historical figures still reverberate today. The American Civil War is one of the great defining events of American history, and George Gordon Meade had a strong influence on how that war played out. What would have happened if he had not led the Army of Potomac to victory at Gettysburg? What would have happened to the nation we know today?

I was honored to be one of the speakers. I kept my remarks brief (to the palpable relief of the crowd). I quoted William Faulkner, who once said, “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.” I remarked on the irony of how easy it is to realize the truth of that when you’re in a historic cemetery where all the figures from the past are indisputably dead. But the history they helped create is a living thing, and the events involving these historical figures still reverberate today. The American Civil War is one of the great defining events of American history, and George Gordon Meade had a strong influence on how that war played out. What would have happened if he had not led the Army of Potomac to victory at Gettysburg? What would have happened to the nation we know today?  Other speakers pointed out that by honoring George Meade, we also honor the thousands of soldiers who fought with him and under him. It was a huge, bloody, ugly war, but it ended with the nation intact and slavery abolished. Anyone who has been following the controversies over the Confederate flag, Confederate war monuments, and even the still-ongoing struggles over civil rights understands that the issues raised by that war are still with us, one way or another. But that’s the thing about the past—it hasn’t even passed.

Other speakers pointed out that by honoring George Meade, we also honor the thousands of soldiers who fought with him and under him. It was a huge, bloody, ugly war, but it ended with the nation intact and slavery abolished. Anyone who has been following the controversies over the Confederate flag, Confederate war monuments, and even the still-ongoing struggles over civil rights understands that the issues raised by that war are still with us, one way or another. But that’s the thing about the past—it hasn’t even passed.

The paperback edition of Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg is now available! You can purchase it through

The paperback edition of Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg is now available! You can purchase it through